Two of Europe’s biggest economies are reinstating some form of national lockdown, as the continent confronts a surge in coronavirus cases and deaths.

From Friday people in France will only be allowed to leave home for essential work or medical reasons.

President Emmanuel Macron said the country risked being “overwhelmed by a second wave that no doubt will be harder than the first”.

Germany, meanwhile, is imposing a “soft” national lockdown.

The measures coming into force on Monday are less severe than in France, but they include the closure of restaurants, bars, gyms and theatres, Chancellor Angela Merkel said.

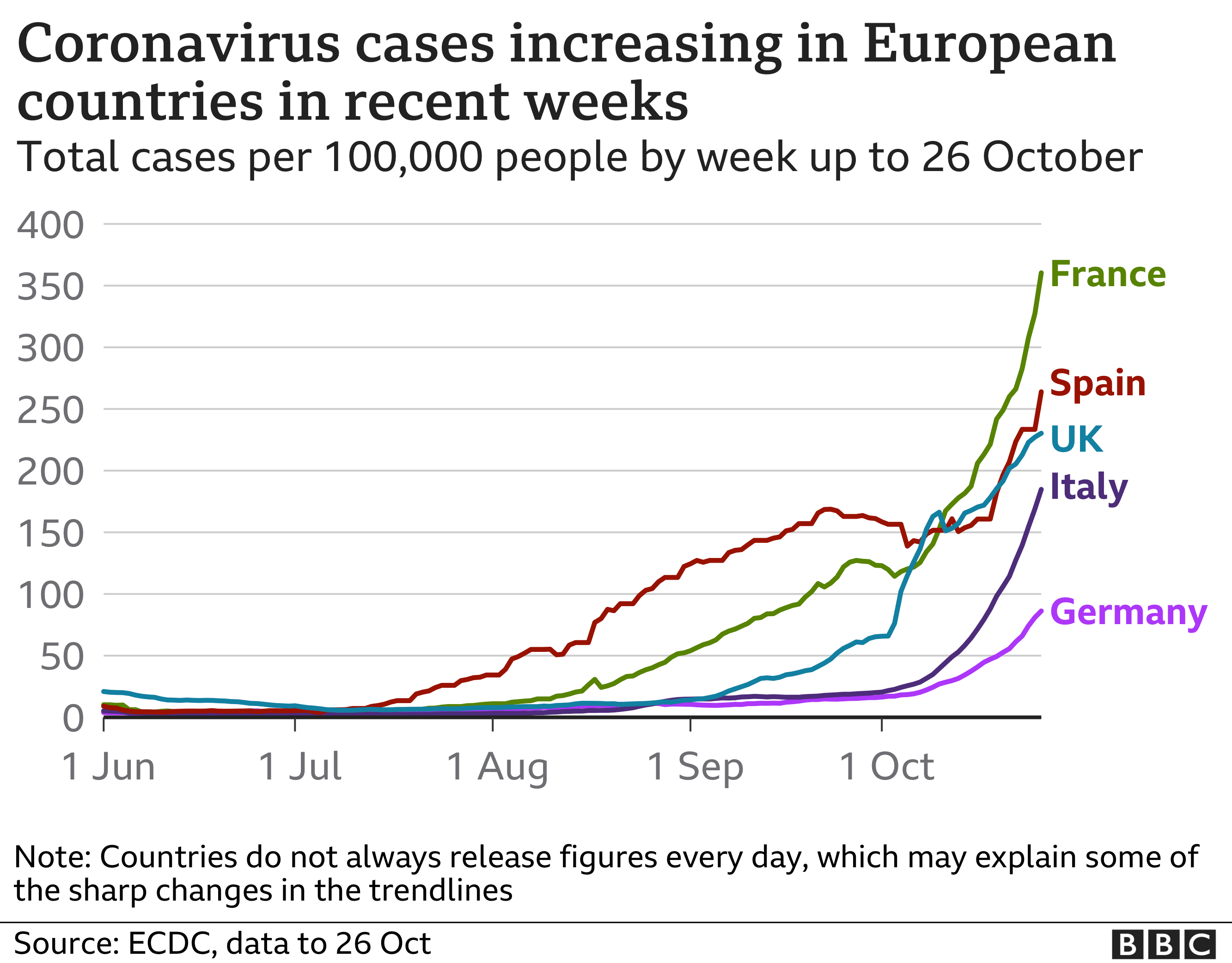

Infections are rising sharply across Europe, including in the UK which on Wednesday announced 310 new deaths and 24,701 new cases.

In England, a new study shows almost 100,000 people are catching the virus every day, putting pressure on the government to change policy from a regional approach.

In France, Covid daily deaths are at the highest level since April. On Wednesday, 36,437 new cases and 244 deaths were confirmed.

German health officials said on Thursday another 89 people had died in the past 24 hours, with a record 16,774 infections.

News of the fresh restrictions being introduced in the European Union’s biggest economies led to sharp falls in the financial markets on Wednesday.

“We are deep in the second wave,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said. “I think that this year’s Christmas will be a different Christmas.”

How did Europe get here?

The first wave of the virus earlier this year hit some parts of Europe incredibly hard, while other areas were able to escape the worst.

Italy, Spain, France and the UK were among the worst-hit nations, with all imposing strict national lockdowns that over time brought cases, hospital admissions and deaths down to a very low level but ravaged economies.

Restrictions started to be lifted in the early summer, with non-essential shops, bars and restaurants reopening, and travel restarting. In August, cases began to rise again too, with a major acceleration in recent weeks that has alarmed policymakers.

Countries that were not hit badly by the first wave – such as the Czech Republic and Poland – have not been spared this time, with experts warning of alarming infection rates across much of the continent.

What are France and Germany doing?

In a televised address on Wednesday, Mr Macron said that under the new rules, people would need to fill in a form to justify leaving their homes, as had been required in the initial lockdown in March. Social gatherings are banned.

But he made clear that public services and factories would remain open, adding that the economy “must not stop or collapse”.

“Like all our neighbours, we are submerged by the sudden acceleration of the virus,” said Mr Macron.

Meanwhile in Germany, Chancellor Merkel said her country had to “act now” and called for a “major national effort” to fight the spread of coronavirus.

Addressing parliament on Thursday, she said: “This pandemic brings the question of freedom to the fore. Freedom is not every man for himself, it is responsibility – for oneself, one’s family, the workplace. It shows us we are part of a whole.”

While Germany has a lower infection rate than many other parts of Europe, the speed with which the virus has been spreading in recent weeks has alarmed the government.

“Our health system can still cope with this challenge today, but at this speed of infection it will reach the limits of its capacity within weeks,” Mrs Merkel said.

A partial lockdown will now begin in Germany on 2 November and last until 30 November under terms agreed by Mrs Merkel and the 16 state premiers.

Bars and restaurants will close except for takeaway, but schools and kindergartens will remain open. Social contacts will be limited to two households with a maximum of 10 people and tourism will be halted.

In terms of economic help, smaller companies and the self-employed badly hit by the lockdown will be reimbursed with up to 75% of their November 2019 takings.

What’s the situation elsewhere in Europe?

Although cases are rising across Europe, not all countries are opting for national lockdowns.

Italy, which was the European epicentre at the start of the first wave of the virus, has already introduced new restrictions which will be in place for a month.

All bars and restaurants across the country have to close by 18:00, although they can provide takeaways later. Gyms, swimming pools, theatres and cinemas have to close, but museums can remain open. Gatherings for weddings, baptisms and funerals are banned.

Schools and workplaces are not closing but many secondary schools will switch to distance learning.

Spain began its nationwide curfew on 25 October after the government declared a new state of emergency. People in all regions, with the exception of the Canary Islands, have to stay at home between 23:00 and 06:00.

According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, the Czech Republic has the worst infection rate on the continent at 1,448 cases per 100,000 people over 14 days. It has imposed a partial lockdown.

Belgium, which has Europe’s second-worst infection rate per capita, has reported its highest number of hospital admissions for Covid-19 since a peak on 6 April. There are 5,924 patients in hospital with the virus, 993 of whom are in intensive care. In a national address on Wednesday night, Prime Minister Alexander De Croo described the situations as “critical”.

The Republic of Ireland went into a second national lockdown earlier this month for a six-week period.

How about the UK?

Cases, deaths and hospital admissions are all rising fast in the UK but the government has stated it is against imposing another nationwide lockdown on England.

Instead, earlier this month, officials announced a new Covid tier system, which enables regions to go into localised lockdowns.

A number of areas, including the city of Liverpool, are in the strictest category – tier three.

Wales has begun a 17-day “circuit breaker” lockdown, with all non-essential retailers in the nation ordered to close and people only allowed to leave home for certain reasons.

The UK nations’ devolved administrations have the right to set their own policies around Covid restrictions.

bbc.com

pixabay